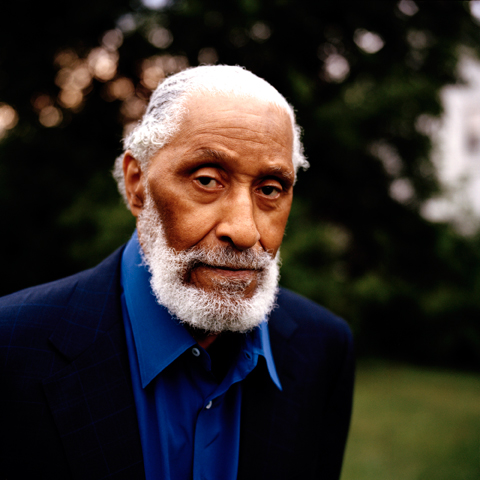

Q&A: Sonny Rollins

Sonny Rollins has been playing jazz in front of audiences since 1941, when he was 11, and “Saxophone Colossus,” his nom du jazz, is well earned to say the least. At 79, when many of the players he came up with are either dead or dying, Rollins, not unlike Bob Dylan, remains a true road dog and inspiration to new players and listeners alike. And to say the least, it was our great honor to talk with this living legend, who we found to be one of the coolest, most interesting people we’ve ever had the pleasure of speaking with. Here, Rollins talks about the dilemmas of present-day jazz, yoga (which he’s been doing every day since 1968), how people almost instantly forgot to be nice after 9/11, and some band called The Rolling Stones.

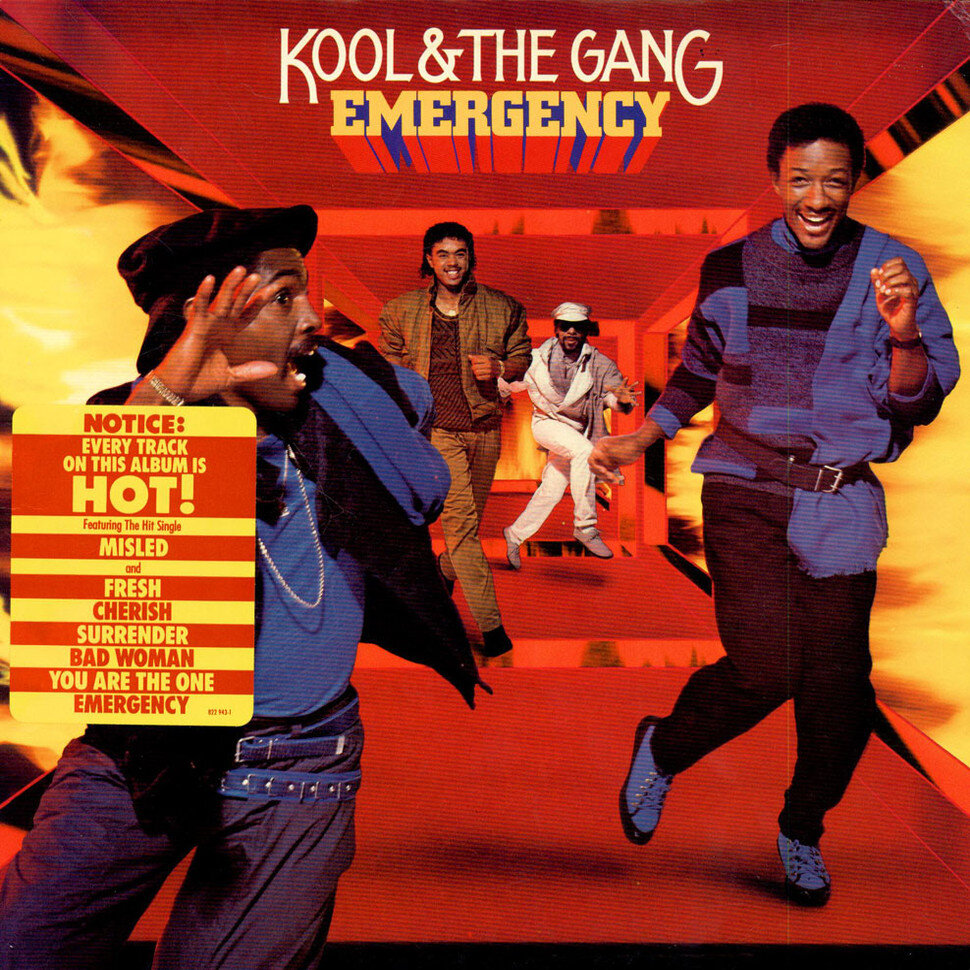

Obviously, your credentials in the jazz world stand for themselves. But maybe not what everybody knows is that it’s more than likely that even the most jazz-ignorant listener has heard you before, performing the sax solo on The Rolling Stones’ “Waiting On A Friend,”which, not to blow smoke, might be one of the great sax solos of the entire rock and roll canon. When was the last time you heard that record?

A hundred years ago. I’ll tell you something funny: Some years ago after that record came out, I was shopping in the supermarket and they play this music, you know, pop songs. So one day, I heard this song and thought, “Hey! This saxophone one player on this record, he really sounds like something.” Then I realized, it was me. I know some people like that record a lot, though, and think it was the last good one they made.

Do you think that rock n roll is still a way into jazz for young people? If not, what is?

It’s a very difficult question, because these days we have so much music. [In addition to all the other genres that have always been around] we now have what they call world music, which incorpates several styles and throws em all together. But it’s an examination I’d like to make. What I’m trying to do is, coming up as a jazz player, I’m looking at creating a music which is universal — in the sense that for the rock and roll crowd, I feel that I want to be able to move them also. I don’t believe that there should be a barrier. I think I showed on that record that the Walls of Jericho can come down, you know? Today, I work on a kind of music where I want to bring together all of the elements. And there’s some things that have to be exaggerated in jazz, and there’s things in jazz that should be de-emphasized. Just like there’s some things that have to be exaggerated in rock, and some things that need to be de-emphasized.

Some people argue that we’re well past that now, though, that jazz, by its very nature today, is academic.

That just happens to be the evolution of jazz as an everyday common music. It was, at first, very much a private music and then it became a music that was acceptable to teachers. But I don’t think it should be academic — I think it should be free, and spontaneous. And rock and roll [still] has that. Just in the style — the style of rock is based on a free expression. But jazz is even more inventive and creative, and it doesn’t rely on the rhythms of rock. I’m going to bring everything back together. I defy you to see that there’s a strong element of the Native American people [running through all this music], and this is what’s going to tie all of this together. Their music has a tie which hasn’t been discovered yet, and when it is discovered and presented to the world and listened to, it’s going to be something which will be timely and express the greatest aspect of music — which is really to bring the world around. It’s the the universal music coming out of the United States.

This is something you’re working on now, a project involving Native American music?

Yes. I am working on it now. I’m still very music-involved, you know — and I’m right in the middle of this project. Some of my friends play golf — playing music is my golf. I’m still trying to perfect my own playing, and in doing so, I keep discovering new avenues.

Your latest record, Road Shows, marks the opening of what it’s safe to assume is a massive pile of live recordings over the last few decades finally seeing the light of day. Just how big is the library of recordings that you’re drawing on here for this series of releases?

I’ve been recording myself for maybe 15 years, conservatively, I’d say. And then there are the collector people who aren’t bootleggers but mostly just listeners, and there’s a lot of that out there, also. I just listen a little portion of what i had to [to put this record together]. I’m not a big person to listen to myself — I listen to as little as possible. When i do Volume 2, I’ll get to it then. [laughs]

In 1972, you took a sabbatical, in part to study yoga. What part does yoga play in your life these days?

I’m still involved with yoga. I do my yoga poses, which we call asanas, but as you age, the body loses its elasticity, so you can’t do what you’d do at, say, 30 years old. So I can’t do them quite to the extreme that I once did. But there’s a lot of other aspects of yoga, such as yoga breathing, I still do all of that. I studied yoga in India in 1968 and then learned quite a bit about the ancient practices of the real science of yoga. It’s something that becomes you; it’s part of the way you live, and i’ve done it ever since. That’s not something that you do for two months and go on to something else.

The anniversary of 9/11, as you know, was just a two weeks ago. Thinking back eight years ago, when you were evacuated from your apartment just a few blocks away with famously just your sax and then played the 9/11 concert, how does the vision of the years ahead that you had then jibe with now? Are you still in the same place?

At that time, it was very interesting; the mood of the country was really different. Everybody was very civil to everybody else. Whether you realize it or not, everybody was sort of traumatized. But everybody was so nice! Everybody was so kind! The epitome of kindness, and what it should be like all the time. I knew, in my mind, that this wouldn’t last. I haven’t analyzed why the human mind has to degenerate to a more hateful, greedy place, but that nice feeling after 9/11 didn’t last. It lasted for a couple of months, and then gradually, people started going back to their more animalistic nature. When you’re my age, you have a different outlook on time: For one thing, you realize that time is so quick.

This episode we call life goes by so quickly. You’re able to put things in perspective and form a picture. I don’t know how to talk about the time since then; it’s just life. There’s much more deeper spiritual things that probably would be beyond the scope of this conversation, so I’d rather leave it at that.